I posted a meme recently which asked, “Do You Talk to Yourself? I know I do, and I know I’m not alone. But the more important question is, “What are you saying to yourself?” Because most of the time, we’re not very kind.

For some reason, we say things to ourselves we would never say to a friend or anyone we like. Our self-talk is overloaded with negative comments, putdowns, and impossible comparisons. Most of the time, it’s about small little things we did or didn’t do. Other times, the negative self-talk becomes much harsher. Especially when we’ve taken a big step. We accept a new position or we are going to give a presentation. Now what we hear is: “You are in over your head,” “What makes you think you are such an expert?” “Others are so much better at this than I am.” “I am a fraud.”

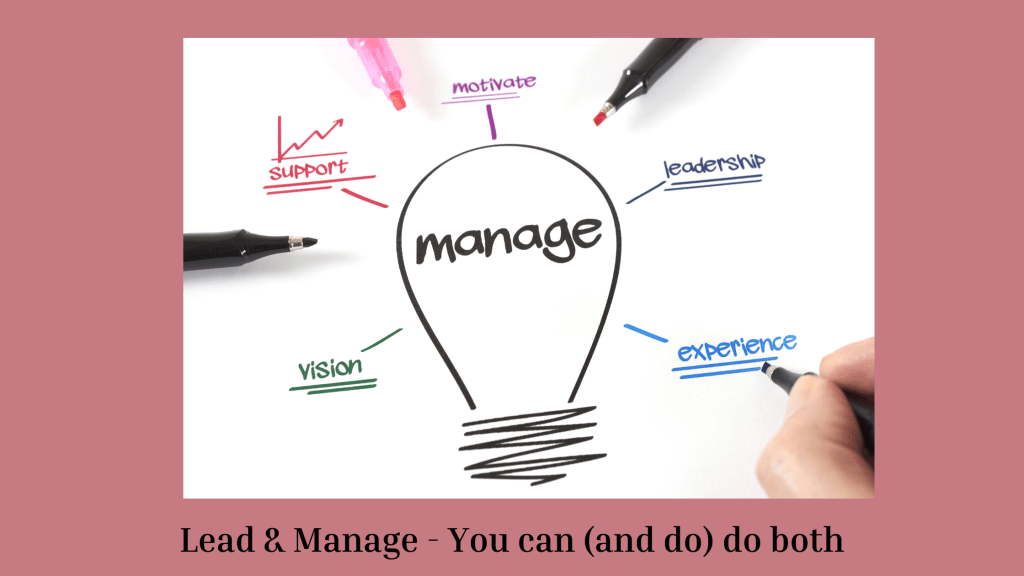

Welcome to Imposter Syndrome. I have written about it before (once in September 2021 and again in December 2021) but it felt like time to revisit it. It’s something both new and experienced librarians face. And if you listen to that voice, it can stop you from taking on new opportunities and keep you from growing as a leader.

To combat this insidious (and erroneous) voice, Marlene Chism wrote How to Push Past the Imposter Syndrome and offers three ways to get over that bleak self-view:

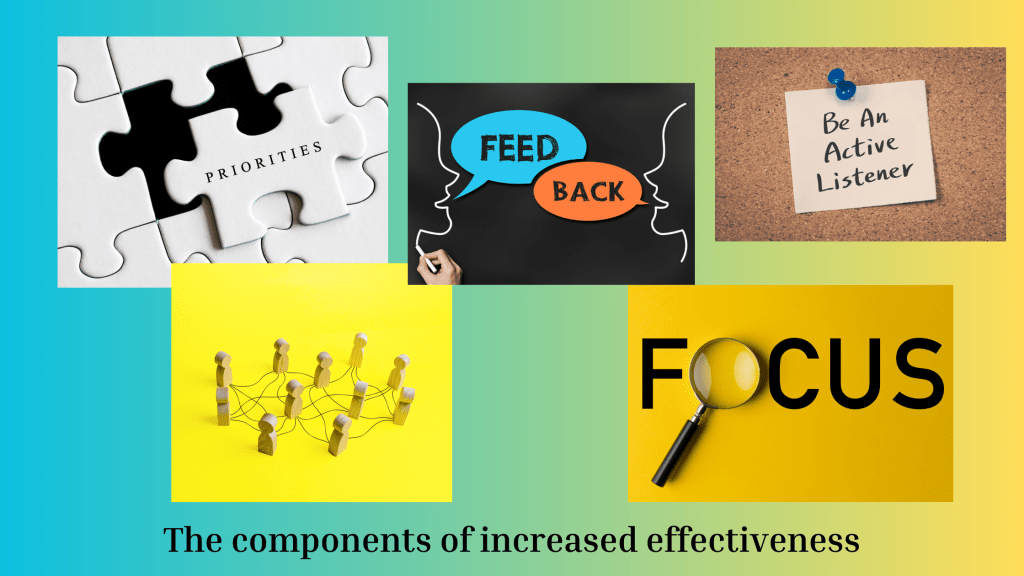

- Shift Your Focus – When Imposter Syndrome arrives, you are focusing on yourself. Positive self-talk is not always strong enough to defeat it. What can help more is to focus on your values, on what you care about. Which of your values will you be expanding in that new position? Talk to someone who is passionate about something you care about and get their views. Chism says you don’t feel like an imposter when “you are giving value or being curious about others.” Shift to see what you are offering.

- Rewrite Your Narrative – Some believe that Imposter Syndrome should be welcomed as the price you pay for growing. According to Chism, accepting that narrative is not good for your mental health. She recommends you see it as your opportunity to learn. Yes, you’ve grown to a new level – but you’ve earned that growth. You’ve done the work, and you deserve to be proud of this next step.

- Stop Competing and Comparing – Sometimes you are “faking it till you are making it” because you’re in a new place, and yes, maybe you are a bit of an imposter because you’re starting out. But remember, this is part of your process for growing. We all have our strengths – and weaknesses. The person who you think is better than you in this new field might not be able to to do what you can in another area. Recognize and accept both your strengths and weaknesses. Think like an athlete and focus on your performance. How can you build your strengths? Are there weaknesses you need to address? Who can help you do this?

Imposter Syndrome will make its reappearance many times in your life. It can be paralyzing if you don’t take the time to dismantle it. Noticing when it has arrived can let you recognize where you are growing. Don’t let it stop you. Failing isn’t fatal. It’s another step in the process. And something to think about: Imposters don’t get Imposter Syndrome.