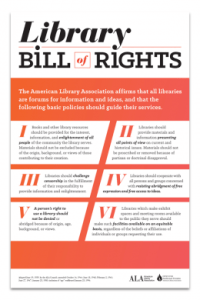

In this day of libraries receiving regular disputes about books in their collection (and ALA has some great resources should this happen to you), it’s important to have advocates for the library who can support you through this process and any other challenges your program may face. One of the best ways to do this is to create and develop an Advisory Council.

When you’re planning, try to make your council as diverse as possible without becoming unwieldy by limiting your board to between 5 and 8 members. First, consider other librarians. You can invite the local public librarian and a college librarian, if there is one in your area, are other potential members. If you are at the elementary level invite a middle school librarian. Middle school librarians should look to high school, and high school librarians invite the middle school librarian.

Next, consider inviting one or two teachers from different subject areas, STEM teachers especially. If you are at the high school level, consider adding a student representative. Reach out to the community as well. Invite parents and local business owners. Inform your administrators, inviting them if they are interested. (And keep administrators in the loop no matter what).

As you develop your plan, start by creating your ask. What will be the purpose of the Advisory Council? How do you see the potential contribution of the members? What will the commitment entail? Before or after school? Evening? Zoom or in-person? Know what you are asking people to do.

Also consider what members will need to know about the library to be effective. This includes an explanation of the Code of Ethics and the 6 Common Beliefs in the National School Library Standards. Add whatever else you believe necessary, depending on the members, and be sure to have these resources available to the members.

At the first meeting, welcome and thank the members for volunteering their time. After brief introductions, review the purpose of the council. Ask what they know and think about the school library. As succinctly as possible, review what you determined members need to know and encourage questions to ensure their understanding.

As a group, develop what the goals of the Council should be. You might want to focus on the diversity of the collection, reviewing the collection development policy, or what changes are needed to ensure the library is welcoming to all. Although you are leading what the possibilities are, be open to their suggestions.

Alaina Love’s post How to Lead a New Team to Success offers a direction for how to continue.

- Listen before leading – Don’t plunge into the tasks. While you want something to show for the first meeting, allow time to hear from the members. You asked them to be on the Council for a reason, but they may have more to offer than you knew. Be open to discovery.

- Share – Set up a Google doc or other method where Council members can report so every one can keep up with what is being done. After the first meeting, for example, you may have them comment on any goals that were discussed. Also, the doc can have a place to post any questions they have that have arisen since the meeting. Be sure they know everyone can respond to someone else’s posts.

- Seek insight –Discover what drives your members. Why did they agree to be a part of the Council? What do they hope to give? What do they hope to gain? What have libraries meant to them. Knowing them as people, beyond their titles, will make them more connected to the team.

- Evaluate and align – The more you learn about the members the better you are at assigning tasks. We all have strengths and weaknesses. You do as well, and the Council is meant to help you do better at leading the library program. By knowing what members like to do and are good at, you not only get the best results but also increase their commitment to it.

- Review – Leaders inspire and inspect. Over time, notice how things are going and assess whether members have been offered the opportunity to give their best. Should you make changes in who is responsible for different tasks, be sure to frame it in the context of feeling they could give more in the new assignment.

- Query, acknowledge, celebrate – Get their input as to how they feel things are going. Instead of asking “how are we doing?” ask, “What can we be doing better?” And celebrate Council’s achievements and those of individual members. Even if you meet virtually, try for an in-person celebration. People stay more invested and active when they are acknowledged.

- Look outward – Council members don’t stay forever and new blood will always be needed to keep the council strong. Encourage outgoing members to recommend their replacement. Be sure to welcome new members and get them up to speed.

Creating and sustaining an Advisory Council takes work, but the benefits to your program and how you are perceived make it worth it. Bringing in diverse perspectives will give you the direction you need to ensure the library is a safe, welcoming space to all and continues to be an invaluable asset to the school.